What follows is a mini-review on nearly all the books I read this year, which will serve as a kind of journal of the year as well. Perhaps in this list you'll find a new book or two to enjoy in 2020.

I will note that I didn't include weekly or special Bible readings on this list, though my focus this year was Genesis through Ruth, and also the 4 gospels and Acts.

This post (Part I) covers the first half of the year, when I branched out and read some books unlike my usual reading habits.

January

1. Can't Hurt Me: Master your Mind and Defy the Odds - David Goggins (Audible)

Background: January saw me exhausted after the holiday ministry marathon and a year of big life changes. After a meeting in southern Taiwan, I took a couple days off and continued south to Kenting national park, to a guest house I have stayed at in the past, a short walk from the ocean. I had encountered David Goggins (on youtube iirc) and heard a bit of his story, which inspired me to go find his book, very different from my normal reading/listening material (as the list below will show)

The Basics: Goggins has an unbelievable life story of rising from a very difficult and abusive childhood to become an ultra-marathon runner and join the Navy Seals, in the process becoming an athlete with incredible fortitude and mental control. The book is his own perspective on his life and struggle to achieve his ever-more-challenging goals to find how far human endurance can go.

The Good: Goggins' story is very compelling, and he tells it straight. It was what I needed to hear "on a secular level" during a very tired and demotivated period, though I didn't go all the way and actually work on the transformational challenges he listed at the end of each section. Your own problems and roadblocks will probably seem less daunting while listening to Goggins' forceful encouragement to not let life's challenges stop you. Goggins' well-known "40% rule" is a good concept to internalize. (When you think put forth all the effort you can, you're probably only at 40% of how far you could really go if your mind wasn't holding you back)

The Questionable:

Note: If you get the special audible version, the unusual interview format of the audio book may be off-putting to some. The friend who helped him, while deserving props for being part of the inspiration of the project, also interjects randomly into the narrative to ask questions or occasionally offer his own perspective, and this can be distracting. However I did very much appreciate that the audible narrator is Goggins himself telling his own story, vs. having someone else read it.

Reviews for this book mention that Goggins' relentless drive leads to a very self-focused narrative, and by the end of the book it does get a little tiring. But Goggins never claims to be a well-rounded individual with healthy relationships, he's someone who takes on endurance challenges and persists far beyond most people's physical limits.

Note that there is a certain level of profanity, which didn't bother me given the context (he's talking about getting into the Navy Seals and running dozens of miles on broken bones, etc.), but just mentioning it for those who find it a problem for various reasons.

The Bottom line: If you need or want a "get up off the floor" kind of book from the life experience of a guy who not only got off the floor but came up out of the basement (carrying a piano on his back), this might be it. Not a light or casual read, but it will probably motivate you to get in better shape or get back into the workout plan you slipped out of, and might help you view your own problems and challenges from a different perspective.

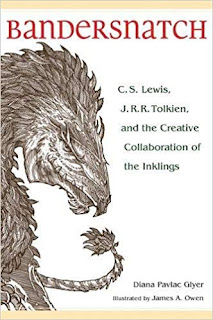

2. Bandersnatch - Diana Glyer

Background: And now for something completely different... I've always been a fan of Lewis, Tolkien, etc., and in late January I spent a bit of time reading up on the history of the Inklings, which led to finding this gem.

The Basics: The author invested much time and effort combing through the correspondence of Inkling members, with decades spent studying their work, to piece together a fuller picture of the group, the individual members, and how it evolved over time than I had encountered before. Here you will learn specifics like how C.S.Lewis seriously influenced the development of the Lord of the Rings, but also more information on lesser-known members of the Inklings which were important to the group itself, and what they thought about each others' work.

The Good: There are books out there which delve into the Inklings, but this is among the best. As a serious Tolkien geek, I was delighted to find bits of information about Tolkien's thoughts and creative processes and how the Inkling community shaped his work, despite Lewis' famous denial that Tolkien's work could be influenced (from which comes the title of the book -- "...you might as well try to influence a Bandersnatch!") Glyer does a very thorough job of showing that Lewis' breezy denial wasn't entirely accurate, and he had deep and significant influence on the direction of the LotR story at a pivotal time early in its creation.

The Questionable:

Not really much downside here. Anyone interested in the Inklings, how the Lord of the Rings series was written, etc., will find much of great value here. The work the author put into this is obvious, and the fruit her effort yielded is fascinating and enjoyable.

The Bottom line: If you like C.S.Lewis, read this book. If you like J.R.R.Tolkien, read this book. If you are interested in the Inklings, read this book. If you are interested about how literary-minded people can influence each others' work in positive and occasionally negative ways, read this book. If you have ever dreamed of being part of a group like the Inklings, definitely read this book!

3. Mere Christianity - C.S.Lewis (Audible)

Background: At the very end of January, having enjoyed some time learning more about the Inklings, I got the audio book of Lewis' Mere Christianity, a book I have read quite a few times.

The Basics: Created from a series of talks Lewis gave on the nature of the faith, Mere Christianity touches on a broad range of topics regarding God, Faith, and what it means to be a believer. The original format results in a comfortable, conversational style, and it's a good reasoned defense of the faith starting from universal principles.

The Good: Lewis is a master of speaking reasonably and coherently about the Christian faith, both about the faith itself and what it's like to be a Christian in the world of his day. To me the most deeply valuable concept here is Biblical Christianity presented as the foundation of one's worldview rather than dependent upon it, a point every believer in this age needs to internalize and keep in mind when facing the barrage of ideologies and viewpoints promoted to us on a daily basis.

The Questionable:

In the half a century since this book was published, the issues society wrestles with have shifted, and thus certain parts of the book are aimed at problems that are less urgently in focus now. There is also a British emphasis on "reasonableness" which is pleasant and edifying but I wonder how C.S.Lewis might have re-written the book had he lived longer and seen the dark societal fruits of the cultural revolution the US and England were going through at the end of his life.

The Bottom line: This is a book all English-speaking Christians should read at some point (it doesn't necessarily translate outside of its language and cultural context well, but that does not diminish its value within those contexts, even several decades later). If you have not read yet it, you should; you are likely to find your understanding of what it means to be a Christian to be strengthened or clarified in various ways by Lewis' clear-eyed thinking and explanations. It's not a long read, and it was a pleasant audio book experience with a good narrator.

February

4. - 9. Six Novels by Charles Williams (The Place of the Lion, The War in Heaven, Many Dimensions, The Greater Trumps, Descent into Hell, All Hallow's Eve)

Background: To wrap up my Inklings kick, I delved into the work of a very important Inkling who is not well known or read today, Charles Williams. As Chinese New Year break had come around, I had several days' time to read, and went on a deep dive. By the time I came up, I'd read 6 novels and decided he has a mad genius.

The Basics: Charles Williams was a prolific member of the Inklings. His works were recognized by T.S.Eliot for their unique talent, but his style is deep and less accessible, and thus their popularity have not endured as have the classics of Tolkien and Lewis, though much of his writing was well known and received in his day. Williams tends to blend and fuse societal and historical archetypes together with spiritual concepts (especially the idea of "substitution" -- as Christ did for man on the cross, but brought into all kinds of different human situations), with a dark-ish plot that builds wildly to a crescendo often involving conflict on a spiritual as well as material plane (and fusing them together) until all culminates in a kind of enraptured apotheosis where anything might happen.

The Good: Williams is an excellent writer, and his fiction is deeply poetic. He skillfully weaves stories that invoke spiritual warfare in a very different manner than someone like Frank Peretti did at a later era--they are always from the human point of view, whether humans as pawns of darkness, attempting to use it for selfish ends, or offering themselves as servants to it, and humans resist with faith and usually a dose of courage and good humor (they are British novels after all). For those who have read C.S.Lewis' "Sci-fi" trilogy, the last book is his attempt to copy Williams. (He was only somewhat successful, but that's a good thing in many ways)

The Questionable: The fiercely poetic nature of Williams' writing can make following the plot become quite a challenge once one nears the climax. One needs to read on a different level, bearing in mind the images and associations carefully built throughout the novel which later begin running rampant and transforming and revealing hidden significances. The novels are not easy reading and they can get very dark (depicting occult rituals, etc) when setting up the novel's antagonists, though darkness is always overcome by the inevitably triumphing light. You will probably find yourself asking "what is going on here" at some point in each novel. For evangelical readers, the way Williams writes about Christianity may seem quite strange or even absent depending on the book, as he is often invoking archetypes of the faith and biblical metaphors rather than the direct approach one usually encounters. This may not be very satisfying if one prefers clarity and explicitness.

The Bottom line: If you have some time, are feeling "literarily courageous" and don't mind things getting dark before the light triumphs, and want to tackle some books that will introduce concepts and images to your mind that you'd not expected to encounter in a member of the Inklings, you might want to give one of these books a try.

10. Bamboo Bends - Sheldon Sawatzky

Background: After Chinese New Year ended we resumed our normal ministry schedule. I was sent this autobiography of a retired missionary to Taiwan by his son who I am connected to through some responsibilities on the field.

[Note: This is neither "When Bamboo Bends" nor "The Bamboo Bends," two other books available on Amazon at the time of this review.]

The Basics: A Mennonite missionary writes his life story including many years of work on the mission field in Taiwan, using the metaphor of bamboo, which in the face of storms, bends and flexes rather than standing stiff and breaking.

Thoughts: This is a well-written personal account which could describe the lives and callings of so many missionaries who heeded the call to Go during that era. Coming from a stable, mid-western background, a missionary goes to Taiwan with the desire to serve God. He meets challenges on the field as best he can, sees some successes and disappointments, marries and raises children overseas, earns his PhD, teaches at a local seminary and moves into denominational leadership and eventually retires having participated in the wrapping up of the Mennonite work in Taiwan. Through it all he remains appreciative of small blessings, and remains a loyal member of his denomination and mission board. He is willing to speak up about certain issues he felt were handled improperly or where he was misunderstood at the time, and does a good job of reflecting the complicated nature of missions work in general, not glossing over the negative but always balancing it with accounts of fruit and God's faithfulness in difficult times.

To me the story was valuable for another specific reason:

As a missionary in Taiwan, I live and work in the context of the legacy of missionaries and mission efforts of Sheldon's era. I never had the chance to meet him personally, but he and many elderly, seasoned missionaries were retiring from the field in the years I first began to visit and fall in love with Taiwan. They left behind a legacy of gratitude in the local church, yet also a vacuum in their wake as they were not replaced by younger missionaries. It was very meaningful for me to read the entire life story of a missionary to Taiwan, and understand the challenges of field prior to my arriving, and the worldview and mentality with which the previous generation of missionaries approached their ministries.

Today we can think of a few things we wish had been done differently, and so it's especially important that we read these stories, and understand to what extent they were pioneers and to what extent they built on the foundation laid before them in turn. These men and women invested their lives on the mission field, and their work bore kingdom fruit and left unsolved problems as well.

For Millennials, the idea of leaving behind unsolved problems for future generations can be a very uncomfortable one, and the idea of being a simple worker for whom that kind of big picture responsibility is simply not on the radar is not always well received. (Indeed, even many church leaders today seem to have embraced with disturbing enthusiasm an unbiblical picture of collective guilt based on even more tenuous associations.)

Thus in 2019 it's more important than ever to hear what our predecessors have to say, and understand them in their own context. Missionaries have never been superheros. These men and women were not cultural or language experts as they went onto the field, though many ended up quite knowledgeable in both areas. There was no over-arching or meta-organization to decide or direct what missionary efforts in an unfamiliar culture should probably look like, or to best predict how work done in certain ways would either aid or frustrate the efforts of subsequent generations of missionaries. Indeed, there is not much like that now either, and probably cannot ever be, and only with the internet have those kinds of meta-level conversations become more prevalent and accessible to a wider audience.

Most missionaries of that era worked hard and faithfully in ways that made sense at the time, as Sawatzky's book depicts, and if hindsight has provided us with insights to which they did not have access, let us not sit on this helpful information and fail to work as hard and as faithfully as they did.

The Bottom line: Some of the details of this book may not be of great interest to anyone not already possessing some knowledge of Mennonite or Taiwan missions history, but I think it's valuable as a well-written account of a life spent serving God overseas. The missionary task is described well by Sawatzky who provides an honest and well-balanced account of the particular joys and challenges of the missionary lifestyle. For that reason I would recommend it to a wider audience who might not otherwise know of it.

March/April

11. Confessions - Saint Augustine of Hippo (Audible)

Background: Having read so many hundreds of pages in February, and with Spring ministry increasing, I did more listening to podcasts and less reading in the following weeks. I did, however, finally tackle a book I had only skimmed many years ago as a high schooler: Saint Augustine's Confessions. I had been unable to get through it at that time, but an audio book with a good reader turned out to be the secret for making it all the way through.

The Basics: Saint Augustine confesses the sins of his youth, and describes his journey to faith. It takes some endurance to get through it all, but there are many points of interest along the way.

The Good: This is a classic literary work of Christendom, and so there is an argument that one "ought" to read it. Either way, I found much of the content surprisingly applicable to our own time. In Augustine's day there are a host of worldviews and spiritual traditions that are competing for attention, and as he describes them one comes to realize that indeed "plus ca change, plus ce la même chose" (the more things change, the more they stay the same). We have our own hedonistic and gnostic rhetoricians today, and Augustine's experience and rejection of them can give us insight into how to face these arguments many centuries later. (There is a particular incident I can only describe as Augustine well into his faith journey, meeting the Jordan Peterson of his day and realizing his rhetorically powerful platitudes are still not enough) Augustine's philosophical interests also lead to some musings on the nature of things from a Christian worldview along the lines of natural philosophy, which I found interesting as well.

The Questionable:

I suppose I'm not supposed to question Augustine, but basically it's a long book and Augustine is a pretty emotional guy. While full of insightful self-critique, in the process of confession he does indulge in what I'd call "wallowing" more than once or twice, and some sections become repetitive. Listening to an audio version helped, as I'd be very tempted to skim past large sections were I reading it in print, but miss some valuable points in doing so.

The Bottom line: To be a well-read Christian, or for a deeper understanding of the philosophical foundations of the West, this is one of those books you need to read. If you commit to it, you are likely to be surprised by many valuable insights about God, the nature of the human soul, the struggle to believe in a pluralistic and rhetorically challenging society, and one very famous figure's journey to faith.

May

12-16. The Dark is Rising series (5 books) - Susan Cooper

Background: For someone who has read quite a lot, the scope of my reading is not as wide and diverse as it could be. For example, I have read the Chronicles of Narnia series several times through, but couldn't point you to any comparable series. I have also become interested in how children's literature inculcates cultural and religious values in each generation. One series written in the 90's which takes aim at the Narnia series was His Dark Materials trilogy, which was publicly acknowledged to be an "anti-Chronicles of Narnia." I had heard enough about that series to decide not to bother with it, but I had heard references to an older series for children/young adults called the Dark is Rising, written within 15-20 years of the Narnia books, and decided to check it out.

The Basics: A classic sort of "chosen siblings" tale deeply rooted in English history and mythology, it has that much in common with the Narnia tales. Where it's totally different is that Cooper writes a very pagan tale where the "Matter of Britain" (King Arthur, Merlin, etc) figures are present and importantly involved, yet Christianity as such is almost totally absent.

The Good: The books are fairly well-written, and they weave together lots of historical and cultural threads with a loving treatment of the local folk culture of the British Isles which has increasingly been lost.

The Questionable:

I have found that Western writers who reject Christianity and try to substitute their own worldview very consistently have a kind of systematic weakness underlying their work; they're trying to ignore not merely the elephant in the room, but the elephant on whose back the palanquin of the West is partly balanced, but trying to get you really excited about some much less comprehensive and fundamental belief system. Materialist atheists are the worst at it, but tradi-pagans aren't much better. Thus I can't take seriously a book or a series with scenes like the following: A clergy member recognizes the tangible presence of evil outside his church, and very sensibly prays to God for protection. In most fantasy books nowadays, this would be treated in a pluralistic way; the pastor's faith would help to fight off the evil or at least delay it, but a buddhist priest or "good guy shaman" would be just as helpful. But this series was written in the 60's, and the British cynicism towards their national church is in full swing, thus the reaction of the main characters is a knowing smirk. "We know the truth about the universe, and it's not your nice little Church of England homilies, but pray if it makes you feel better." But what do they have that's considered superior to faith in the living God, the Messiah at whose Name every knee shall bow in all the universe? On the basis of what greater power will they throw out everything from the conversion of the Roman Empire to Handel's Messiah to holy communion on the moon? Are they atheists who believe it's all superstition and only science can solve this problem? Not even that. Instead they have amulets, and bits of poetic incantations, and wise nature lore, etc. Either the author has simply never been exposed to genuine Christianity (sadly quite possible in England both then and now) or she's being willfully silly.

Having rejected the Biblical metanarrative and Christian worldview, the conclusion of the series is rather weak as well, as all we're left with is nature and the vague elemental forces behind it moving through great cycles. There's no evil, just "dark" and no good, just "light," and neither is inherently friendly to humanity, though light is biased toward freewill and dark is biased toward oppression. Perhaps for people unaware of the Christian worldview, "we've done enough to hold the dark at bay for another long cycle of years" is a satisfying ending. But when compared against the story of Christmas, it gets blown out of the water, something that Lewis captures well in the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The victory of Christ is awe-inducing when one understands what is going on; in comparison, "dark-ish-ness defeated temporarily by old wisdom and the elementary power of nature invoked correctly" simply doesn't have any urgency at the cosmic scale Cooper is staging it in by the end.

The Bottom line: Don't get these books for your kids unless you want them steeped in a very pagan worldview. They might serve as interesting stories for older students who have shown sufficient discernment and can discuss the worldview and cultural/historical aspects. But if you want a fascinating take on Arthurian Britain in a context that acknowledges the pre-Christian mythos of England but recognizes the lordship of Christ (and also brings in the dark religio-scientific influences we've been seeing lately in the world), check out C.S.Lewis' book That Hideous Strength.

17. Taiwanese Folktales - Fred H. Lobb

Background: After the preceding foray into English folk mythos, I was motivated to learn a bit more about the local folk stories here. I started to re-read the biography of the most famous missionary to Taiwan (George L. Mackay), still revered with statues in northern Taiwan, and at the same time I stumbled across a reference to this volume. There isn't a huge amount of literature available in English about Taiwanese culture in specific, and this book probably isn't the best way to begin that journey, but it was an interesting series of stories, demonstrating both local particularities but also universal fairy tale tropes.

The Basics: A collection of folktales, Lobb has helpfully organized them into sections based on the legacy culture (Hakka, etc), and included some modern ghost stories at the end. He's also included notes which mention variations on the tales and some anthropological information.

The Good: These are not someone's opinions, but local stories, so they are "raw cultural data." Reading them can help explain local culture in indirect and sometimes archetypal ways, versus a book on the history of the region. As a set of stories that aren't likely to be told much nowadays, there is some value of having them collected, and available in English.

The Questionable: It's a random collection of tales, and some are much more interesting than others. Some seem to be derived straight from the pages of the Brothers Grimm, except for the East Asian setting, while others are very Chinese, like the drowned ghost a man befriends yet manages to keep from stealing anyone's body. Some are dark and violent, but again, so are the European fairy tales which haven't been Disneyfied.

The Bottom line: This may be more of a niche book, which I'm specifically interested in due to living in Taiwan. However hats off to Lobb for his work in bringing together and publishing the collection, and for anyone interested in Taiwan specifically or East Asian fairy tales in general, this might be a valuable addition to your library.

June

18. The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War - Ben Macintyre (Audible)

Background: An overwhelmingly busy Spring warmed into summer as my home assignment loomed on the horizon, and someone recommended this book to me. I can't remember who it was, but I'm grateful as it was a fascinating, true account of Cold War spycraft which kept me entertained on many subway rides around the time of my engagement to my fiancee.

The Basics: The story of the Soviet KGB spy-turned-counter-spy Oleg Gordievsky, his motivations and handlers, how he was eventually outed by a Soviet-paid mole in the CIA, and the hair-raising adventure of eventually getting him out of Russia and into the West.

The Good: The title doesn't lie--this probably really is the greatest espionage story of the Cold War. It has spies, counter-spies, moles, failed and successful operations-within-operations, competition and cooperation between MI6 and the CIA, and the KGB, fake identities and even cool custom spy gear, and it's all a true story. I listened to the audiobook version, and recommend it as a very good book for listening vs. reading.

The Questionable: Not much to say here. It's a detailed historical book with a lot of Russian names, perhaps reading it would be less enjoyable than listening to it as I did.

The Bottom line: If you only read 3 books about the Cold War spy vs. spy era, this should probably be one of them.

First half of 2019 - Winners:

The two winners for the first half of 2019 were Bandersnatch, and The Spy and the Traitor. I highly recommend both, and suggest getting the second as an audiobook.

(Continued soon in Part II)